The Art of sustainable bean counting

Two-part Guest contribution by Simon Pfister, Managing director of Foundation Green Ethiopia. Read the second post here.

In „professional“ organizations, bean counting (i.e. bookkeeping, financial accounting, measuring costs, etc.) is one of the most important activities. Important in terms of how much C-level* attention it receives, and the power it has to stop investment ideas, to cut into development projects, and to lay off people. The history of this importance can be traced back to e.g. 1511, when the Fugger conglomerate asked its accountants for balance sheets; or to Karl the Great, who demanded an annual report including a list of assets in the year 795; or even further back to the Sumerian, who had “books” accounting for bread and beer around 3500 B.C.

Bean counting seems therefore to be applied broadly and since ages and, despite its sometimes negative reputation, was and remains very successful. Why so? I think that this success is rooted in the fact that having solid information about how the beans grow today is one of the necessary preconditions to grow more beans in the future. Therefore having solid, reliable information which in professional organizations oftentimes relates to financial information - is a prerequisite for making decisions. What’s more, I think that the true value of financial accounting is its ability for labeling every activity with a price, therewith offering a single-dimension comparison of ‘facts’. In turn, this simplifies decision-making by to an assessment of activities and ideas regarding their financial effectiveness and efficiency (i.e. more profit, more equity). Obviously, sufficient revenue, positive profits and accumulation of equity are not per se negative – I think everyone who has worked for a company in financial problems or has been laid off would agree. However, a growing number of people also agree that even though focusing on the financial aspects as representative of the economical dimension might be effective, such a one-dimensional approach falls short of assessing complexities of certain decisions. So they demand for sustainability-oriented decisions, which extend the financial, i.e. economical dimension, by including the social and environmental dimensions. And only if all three dimensions are considered in a decision process can sustainable organizations, projects and societies arise. In this, bean counting can serve as example of how important solid information is for making decisions. But the scope of future decision processes should move beyond the scope of traditional bean counting and include social and environmental information in addition to the economic information.

So we agree on adopting multi-dimensional decisions, and to that end take into consideration more than just financial facts. But how do we actually do this? How do we account for positive or negative social aspects? Or for environmental aspects? If everything has a price, i.e. is mapped into the economic dimension, the assessment is simple : more profit and increasing equity is good, lower profit and declining equity is bad. But we want to move beyond this simplicity, we want a more comprehensive assessment of social and environmental facts. If we look at the current discussion about the right mix of energy sources as an example, it is clear that a simple “more-is-good and less-is-bad” thinking is insufficient.

The challenge of multi-dimensional decisions

The discussion on changes in energy sources (Energiewende) that is ongoing in many European countries is highly critical for everyone of us, because we are all consumers of electricity, but we have relatively limited options to choose from. At the same time, this discussion has very long-term effects and includes a lot of stakeholders with unclear decision powers. So, in order to achieve a sustainable decision, different balances must be discussed and agreed upon where the advantages and disadvantages of different alternatives are considered, and where, instead of giving them a price, we come up with a statement about which mix of alternatives is acceptable and bearable. When this “Energiewende” discussion started, after the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan in Spring 2013, many governments immediately suggested to reduce the amount of energy from nuclear power, by immediate shut-downs, shortening the years of operation, etc.. However, shortly after these announcements, the discussion shifted into how to replace today’s nuclear energy production, immediately leading to a political discussion about acceptable levels of additional CO2 output, to what extent windfarms may influence landscape sceneries, or to what extent photovoltaic systems may be supported by government subsidies. In the meantime, some countries returned to nuclear energy as an acceptable option. In short: moving away from the status quo and finding a new energy balance is not at all simple.

I assume that if these discussions allowed for even broader balances, controversies would be even more controversial. What if energy efficiency or distributed energy production tok a greater part in the discussion than they do today?Or what about allowing for unorthodox ideas, such as limited availability of energy for private houses during certain hours, which is a reality for many people in developing countries? Such ideas would bring very new aspects into the equation of balancing alternatives. Personally, I strongly believe that we need such out of the box thinking in order to allow the next generations to fulfill their needs in somewhat the same way as we use resources today to fulfill our needs.

Moving into practice

So what does all this mean for an organization or a project? How can ‘sustainability’ be reached? What are the applicable benchmarks, best practice approaches, and relevant measurement, assessment and management tools? My research, covering 250 NGOs in Switzerland and abroad, looked into frameworks for generating systematic sustainability-oriented decisions, i.e. how to omit the pricing of different alternatives and instead systematically assess the different options to find acceptable balances. The results suggest that above all else, organizations and projects should strive for sustainable development rather than for sustainability as a specific level of balance. The two main reasons being that:

- First, concepts of sustainability change as new research offers new insights about best possible balances, or technological changes minimize the disadvantages of one option and influence what is seen as the best possible balance.

- Second, sustainability is always subjective. The balances are never objective since they are influenced by beliefs and ethics.

So moving from the current status (with low sustainability) to a better sustainability level is a development process with continuous improvement cycles instead of a single, immediate jump to a perpetual best possible status. And if an organization agrees that sustainable development is an ongoing process, any measurement approach should foster a cycle of collecting information, discussing these results, collecting feedback, and adapting activities so that an improved situation is achieved in the following cycle. Besides invoking a continuous engagement in sustainability tasks, sustainability measurements should focus on aspects that are most critical and that offer significant leverage, i.e. little effort with big impact. Focusing my analysis on NGOs active in development aid projects, the following four levels meet criticality and leverage best:

- Project initialization (i.e. at project idea and project preparation stage),

- Project results (i.e. achieved output, outcome and impact of project intervention),

- Organization (i.e. optimizing the portfolio of projects as well as internal operations),

- Fundraising (i.e. securing the best possible funding to conduct all activities as planned).

Since all other activities of NGOs may potentially influence sustainability they must also be seen as important. For example, hiring sustainability-savvy project managers is important but their influence is most likely only within the frame of the project that somebody else decides upon. Therefore, deciding on sustainability aspects that are relevant for the project during initialization phase, or selecting a source of funding that shares the NGO’s philosophy of achieving sustainability may span discussions much broader than what the project manager is capable and/or allowed to influence.

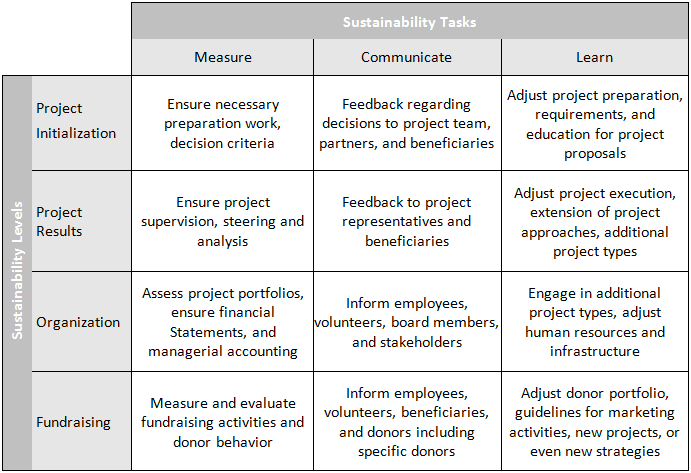

Combining the idea of sustainability levels and sustainability tasks, I proposed a two-axis framework that allows an NGO to continuously assess, discuss and improve sustainability. The data from these 250 NGOs and different statistical analysis indicate that such an approach supports sustainable development more comprehensively than benchmarking with groups of similar organizations or projects, or than linear regressions of best practices.

Figure1: Sustainability Measurement Framework for Development Aid NGOs

including Objectives for each Matrix Field (Pfister S., 2014)

While the research proved that such a matrix is a strong tool for NGOs to improve the sustainability of their projects and the overall organization, success requires proper implementation. The first step requires that the organization defines its (current) understanding of sustainability. In order to do so, it must express its beliefs and ethics regarding environmental, social and economical balances, either through organizational measures such as vision and mission statements, or through sense-making discussions. One example of such pre-required clarification may be whether the NGO should use electric cars or cars with internal combustion engines. Both bring open questions, either regarding how the electricity is produced and future waste from batteries is handled, or regarding where the oil is coming from, which technologies are used and which risks onto the environment and societies are associated with the its extraction and consumption. And once the organization defines their understanding of sustainable development, it must also define measurement figures, reporting structures and feedback options for each of the matrix fields. This is a complex, difficult and highly controversial task, which shall be further discussed in a second blog entry in early October 2015.

Conclusion

So is planning, measuring, and improving the sustainability of a development aid NGO more an art or a science? I am sure that it is, first and foremost, a question of courage. Courage to define its own approach to sustainable development, i.e. to define the environmental, social and economical balances, thereby accepting certain disadvantages and leaving out certain advantages. And also the courage to measure results regarding these balances, transparently distribute this information and allow for feedback, i.e. accept the pressure to re-discuss the balances over and over again, spending precious time and resources which will then lack for other important activities. Nevertheless, I personally believe that such efforts pay off, and different positive examples of NGOs, companies and communities prove so. I hope that you are also inspired to continuously count beans, not for the sake of the beans and not from a financial dimension only, but for the sake of having the necessary economical, social and environmental information that encourages us to take tough decisions towards sustainable development.

* Referring to the Executive level: CEO, CFO, COO, etc. (Editor’s note)

About the author - After 15 years of practical experience in consulting and financial responsibility for international sourcing, Simon Pfister finished his Ph.D. degree at the University of St. Gallen in 2014. The dissertation researched sustainability measurement for development aid NGOs. Today, Pfister is part of the faculty of the University of St. Gallen for managerial finance and general business administration. In addition, he supports different companies and organizations regarding financial management and sustainability. Pfister also serves ass managing director for Foundation Green Ethiopia, a charitable NGO planting more than 5 million indigenous trees annually in rural Ethiopia and supporting their agricultural development.